a fascinating medieval society

Of the 42 countries where I travelled in as a businessman or tourist, Yemen in the nineteen seventies was by far the most fascinating. Even flying into Yemen was an adventure. I was the export manager of the Sri Lankan subsidiary of Unilever, the giant Anglo-Dutch foods and detergents multinational corporation, and the Sri Lankan company had just begun exporting cooking fats to the Middle East. It was just before the 1973 Arab-Israeli Yom Kippur war and the oil-rich Arab states (not Yemen though, where no oil was found at the time and remained very poor) had already started using oil as a political weapon and suddenly become very affluent, with the arrogance that goes with it.

It was September 1973, I had completed a six month management training programme with Unilever in the UK, and my plan was to first visit Jeddah in Saudi Arabia, then Hodeidah (also called Al Hudaydah) in Yemen and later all the smaller Persian Gulf States. I first needed an entry visa for Saudi Arabia and I duly went on an early morning to the Saudi Visa Office at 17 Elton Street, London, to join a long queue of British businessmen, dressed in business suits and with leather brief cases, patiently standing along the pavement at the entrance to the office. The queue was hardly moving and at around noon a man emerged from the office and berated the visa-seekers, shouting “Now finished for the day, go, go …” Frustrated, I contacted our Saudi agent in Jeddah and he said that he would obtain a visa and bring it to the airport. I went back to the Saudi visa office and asked the Visa Officer for confirmation of this procedure. He curtly told me: “If your agent says so, do it”. His sarcasm was lost on me so I went again to the airline office and was told that I could not board a plane to Jeddah without a visa in hand. Back I went to the Saudi embassy for the visa with supporting business credentials. “It will take a few days for your visa. Nothing can be done in a hurry” said the reprobate. There were special rules for non-Muslims.

I changed my tickets, omitting Jeddah and travelling first to Hodeidah. Hodeidah could not be reached direct: I would have to transit from Asmara, then part of Ethiopia. There was only one flight a week from Asmara to Hodeidah, and I duly arrived in Asmara on Ethiopian Airlines on October 01, 1973, to catch the Yemeni Airlines weekly flight to Hodeidah. Asmara (now in Eritrea), was a small airport and the only open counter that day was for Yemeni Airlines. We asked for our flight and the man pointed to a small 40-seater plane lying in the runaway in the blazing sun with parts being removed by half a dozen mechanics. The plane needed repairs and we waited patiently. The little airport was full of noisy locals and a few British travellers. One was a young British woman who nervously asked me what was happening. It transpired that she had applied for a job as a nurse in a hospital in Hodeidah after reading an advertisement in an English newspaper. Of what I knew of Yemen, it was not a place for a lone foreign woman but I kept my thoughts.

By about 7.00 p.m. the Yemeni Air representative was putting up shutters in his office and preparing to leave for the day. The handful of foreigners in transit surrounded him and demanded an explanation. “Come tomorrow, we will see”, he blithely told us. We mobbed him and refused to allow him to leave, demanding accommodation for the night. He led us to a van parked outside and booked us into a small hostel in the town.

The next morning we arrived at the airport and again waited with patience. Patience is demanded of the traveller to strange places. By afternoon it was announced that the flight was ready. The hoard of noisy locals rushed out first, followed by us. The air outside was blazing hot. There were no numbered seats and the plane was soon full. The locals carried huge cloth bundles full of goods and many had cane baskets with live chickens. There was no room for all this heavy baggage and soon the aisle was full of this. About half an hour later the pilot came aboard. He was a lanky European dressed in khaki shorts and was bare-chested. He screamed at the passengers in a local language and started throwing the baggage and baskets in the aisle on to the tarmac. Then he went into his cabin and locked the door. The passengers immediately clambered out and brought back their baggage. A little later the air hostess entered. She was a big, dark young woman dressed in a large black gown that covered most of her body. She locked the plane door, ignored the passengers and went into the pilot’s cabin and locked that door behind her. We were now ready for take off.

The plane took off like a heavy goose, straining to take wing. Once it rose in the air it was barely skimming the palm trees, labouring to reach altitude because of its weight. People all around me were counting beads and saying prayers. There was nothing to do but wait, patiently. My worry was that my agents would miss me at the airport because of these unscheduled delays.

I need not have worried. The Yemenis know their country and its ways. As I descended the gangway of the plane, three men in local costume came up, inquired my name and then kissed me on both cheeks in turn, beginning with the oldest man. They took my luggage and we went through Customs and Immigration like a breeze: the Shammakh brothers had bought them over in advance and got approval for them to come up to the runway. The rather bare airport was full of noisy locals. Before leaving, I looked around for the British nurse. She was agitated as there was no one to meet her and it was getting dark in the evening. I asked the Shammakh brothers whether we could take her to her hospital. They did not welcome the idea of helping a foreign woman but agreed merely to oblige me. We found the hospital and it was closed for the day without a soul in sight. We left her there and went away as my friends wanted nothing more with her.

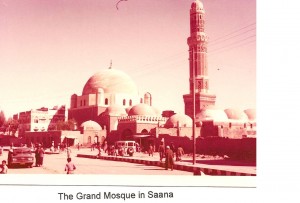

Yemen is said to be one of the oldest civilisations, meaning it was one of the regions of the earth where hunter/gatherers had taken to farming and settled life 12,000 years ago. You could not imagine that now. When it ceased to be part of the Ottoman Empire after its dissolution in 1918 after World War 2, Yemen became an independent nation. Long before the American neo-conservatives, and before President Ronald Reagan discovered that “Government is not a solution to our problem, government is the problem”, the Yemenis had agreed that “Less government is good government”. Following this credo, even in Ottoman times, the Central Government confined itself to the cities while the real management of the country was in the hands of powerful local warlord tribal leaders, some of whom claimed to be Imams[1]. In US terms, these warlords would be the large corporations that control most of the US economy and influence the government through their lavish political spending. As is to be expected, with little government in Yemen, there was very little education, few public services and social services, and mass poverty while the rich and powerful ran the nation for their benefit. People took what they could, if they could get away with it. However, the moderating force in Yemen was Islam, which provided certain guidelines for conduct and behaviour and obligated charity for the poor. It created some form of social harmony, though it was brutal towards women.

Al Iryani was President of North Yemen in 1973 and he was trying to modernise society with some elements of parliamentary government and liberalisation of social conduct. This did not suit the neighbouring fanatical Wahhabist Saudi regime and the puritanical local tribal leaders and, in a forerunner of what was to happen later in Afghanistan, he was removed and replaced the next year by a more authoritarian conservative, Col. Ibrahim Mohamed al-Hamdi. We were to glimpse him briefly a few years later. I was travelling by motor car with the Shammakh brothers in Saana. A motorcade with military and police escorts was seen coming on the road. All other vehicles moved out of the road to the grass verge and the Shammakh brothers got out and stood to attention outside their vehicle till the big man passed us, giving us a fleeting glance of the local lord.

There were two Yemens at the time: North Yemen and the Peoples’ Democratic Republic of Yemen in the south. The ancient commercial port of Aden was captured by the British in 1839 and the rest of Southern Yemen was made a British Protectorate ruled by the local tribal leaders. Aden was an important link for control of Britain’s vast Asian colonies and it was made a Crown Colony governed from India. The Cold War enabled the South Yemenis to revolt against the British with arms supplies from the Soviet Union. Two national liberation groups fought the British till they withdrew in 1967, and then fought each other. The National Liberation Front took power and set out to develop the backward country and introduce modernisation. Since the nation had displeased the West by becoming independent of Western imperialism, it received no international aid. The South Yemeni government had to turn for assistance to the Communist states and hence designated itself a “communist state”. The international isolation of the country outside the communist bloc created a paranoid government suspicious of all foreigners. An extensive secret service kept a watch on all citizens who might engage in anti-government activity. It had become a police state.

My departure from Yemen would be through Aden, which had an international airport serving carriers to many parts of the world. The name of the company the Shammakh brothers managed was called Yeslam Salim Maasher and originated in Aden. As the so-called communist government restricted private business, they had moved their operations to North Yemen though the senior member of the company, Salim Maasher, the uncle of the Shammakh’s, still lived in Aden and directed some of the business. All of them hailed originally from Hadramaut, a region is South Yemen which had a history of seafaring and trading in the Indian Ocean for over a thousand years. The traditional sarong worn in many coastal regions of India, in Sri Lanka, Burma, Malaysia and Indonesia, may have had its origins in Yemen where practically all males wore the sarong. In North Yemen, in addition, the sarong was held up by a broad belt into which a large curved dagger was usually lodged. This decoration had been prohibited in the South by the British. In addition, most people sported a black coat. What the women wore could not be figured out as they were all covered in a black burqa, if they were ever sighted out of their homes.

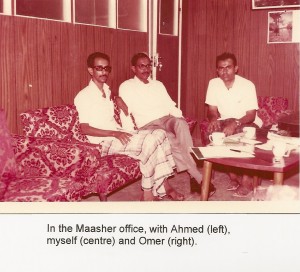

The Shammakh brothers who managed the import/export firm of Yeslam Salim Maasher were astute businessmen and honourable gentlemen. The elder brother, Omer Mahfood Shammakh, was the head and was an affable middle-aged man with a ready smile. Ahmed Shammakh, the second brother, was the only English educated one and was the translator in our talks. The name of the third eludes me and I was not sure of his relationship but he was our motor vehicle driver. Though the country was very poor compared to the rest of the Middle East, with a population of about 15 million, the Shammakh brothers built a cooking fat business for us that was worth about a million US dollars a year. With their knowledge of the local market, we developed a cooking fat with a taste, smell, texture and a packaging that was ideal for the local market. It carried the brand name of Palm Island Vegetable Ghee, a name I invented and was proud of for its success in the Middle East at the time.

Our close friendship was initiated by me through correspondence by letter and telex (then the only means of fast business communication). It prospered with my annual five day visits between 1973 and 1978. During each visit our routine was the same. First, discussions about the market and deliveries were held in their office in Hodeidah. Then, the brothers would take me on a tour of the markets covering Hodeidah, Saana and Taiz, the only three cities connected with motorable roads. I had all my meals with my three friends throughout every stay. I was the only foreign business associate so honoured by them at the time. Their wheat salesman from France was also in the same hotel I lodged in but he was ignored after business meetings. Most Europeans would find it difficult to accept their lifestyle.

Tarmac roads and motor vehicles were still a rarity in the country, though small fleets of trucks operated form Hodeidah port transporting imported goods to these cities. The construction of the three main roads is a tale by itself. They were aid projects by three foreign powers intent on making a local presence: USA, USSR and China. They encountered unforeseen challenges besides the harsh terrain. Local tribesmen, who walked about with their old rifles the way English country gentlemen use walking sticks, took pot shots at the foreign engineers when the road approached their territory. Only the Chinese had the resolve to finish their road and left a testimony to their bravery: a Chinese cemetery was erected near the highest point on the road for the sacrifices of forty Chinese engineers.

We travelled in a large station wagon owned by the Maasher business. Ahmed sat in the front seat with the driver. Omer Mahfood and I sat in the rear seat with a bundle of fresh qat between us to chew on during the journey. The tender leaves of small branches of this local plant are chewed slowly and it acts as a mild stimulant that encourages conversation and a relaxed attitude. Life without qat[2] in the afternoons would be unimaginable for a Yemeni man. It is harmless and is legal in UK and most countries, except in the US where it is designated a narcotic and prohibited. Chewing qat in a group is a daily social activity for men.

On the very first day of travel from Hodeidah to Saana, I was fascinated by the scenery. The country was mostly barren desert with mountainous regions. Interspersed we occasionally saw patches of green cultivation where there was an oasis or deep-water boreholes. Sometimes we would see a small caravan of camels crossing the desert. I missed my camera which I had left in London with my wife who was still there and I told Omer that I needed to purchase a camera. He merely said that he would see how it could be done but wanted to know what kind of camera I wanted. I wanted a Canon SLR. The next morning, when I awoke in my hotel room in Saana, there was a brand new Canon camera in its original packing on the table. At breakfast, I asked Omer how much it cost. He looked at me displeased and said: “Brother, please remember you are my guest’. I realised that it was offensive to decline gifts given as part of Arab hospitality. In future, I would always bring specially handcrafted silver boxes for office use from Sri Lanka for all my Arab business partners in the Middle East to complement the expensive gifts of gold ornaments and wrist watches which I knew awaited me.

Men in conservative North Yemen greeted each other on meeting with kisses on both cheeks. Male friends would even walk in public hand in hand though homosexuality was unknown. Women were not seen in public except as ghostly figures in black burqas and were never approached by men. I was told on one occasion that a foreign doctor was killed by a family because he tried to medically assist a woman dying at childbirth.

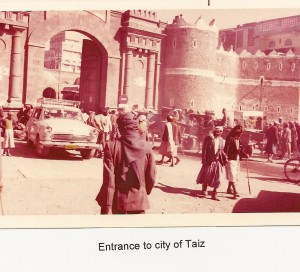

Two incidents that occurred during my visits to Yemen will remain in my memory. On one occasion we arrived after 6.00 p.m. near Taiz. Saana and Taiz are both ancient fortress cities surrounded completely with massive protective walls with enormous gates as points of entry. Omer told me that the city gates were shut after 6.00 p.m. and the Town Guard would fire upon anyone approaching the main gate after that hour. We stopped at a roadside hostel outside which a line of trucks were parked for the same reason. The hostel was a series corrugated iron sheds with three tier iron beds and no other furniture. The inside smelt like a goat shed with unwashed truck drivers and labourers. But it was the only available resting place for the night and the nights were very cool. Without taking out my suitcase for a night dress, I slept in the lower tier of a bunk bed wearing my European suit. Waking up, I saw Omer and asked him where the toilet area was located. He smiled broadly and took me out, waved his hand towards the sandy desert, and said that his was only available toilet. I suppressed my urge till we reached our hotel in the city.

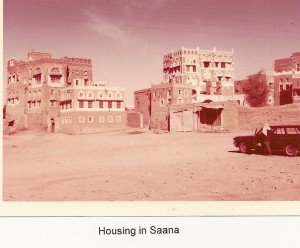

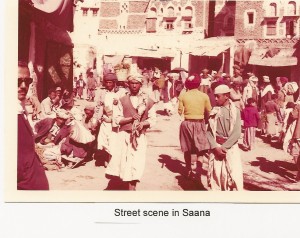

The big cities were crowded with multi-storied buildings made of mud brick with winding narrow alleys in between. As rain is scarce, these mud brick buildings have lasted for centuries. They are often painted red on the outside and look very picturesque with their numerous and uniformly square windows, looking from a distance like giant pigeon coops. The streets are busy during the day with people, donkeys, camels and push carts with goods. But by evening it was quiet. The men would sit around on beds (with ropes stringed in place of mattresses) on the pavements, smoke a hookah which was passed around the group, and converse. I readily adapted to this form of pleasant relaxation.

On another occasion we had an extraordinary adventure. We were travelling from Hodeidah to Taiz in the late evening. The land on either side of the road was desert, sandy and uninhabited for mile upon mile, without a shrub or any grass. We were approaching a cluster of shacks made of palm leaf when a woman, totally covered in a black burqa, ran across the road. The driver tooted the horn and braked hard but the poor woman, whose sight was probably marred by her all-enveloping dress, would not move away in time and was knocked down.

We got down from the vehicle to help her. Within minutes, out of seemingly nowhere, six rough looking men with rifles joined us. A heated argument ensued with our friends which I did not understand. The woman, who was bleeding from somewhere inside her dress, was carried and placed in the boot of our wagon and three of the gunmen got into the vehicle. We now travelled off-road and into the desert. It was explained to me that we were now heading for the hospital in Mocha, the closest town. We traversed the desert sands guided by our new companions who seemed confident of the way. There was an animated conversation inside the vehicle which was occasionally disturbed by the injured woman who let out an agonised scream of “loo-loo-loo-loo-loooo”. The men would turn back and smack her and ask her in their language to shut up. It was now nightfall and it was very dark when we arrived in Mocha and found our way through inquiries to the hospital.

Mocha was a small decrepit seaport. At one time, a century ago, it was a famous port in the Red Sea from where the bulk of the Ethiopian coffee was exported to the world. This was the origin of the blend that is known as Mocha Coffee in America. The hospital was really a fair sized house and the doctor was a Chinese man. He came out and told us that he could not accept an accident victim without a police clearance.

So off we went to the Police Station. It was a three storied building with wooden stairs. We walked the top floor corridor past some rooms with goats and straw giving out the strong smell of animal urine. The Police Inspector woke up from the camp cot in his room where he was snoozing. He wore a sarong and was bare-chested. His rifle hung from a nail in the wall above him. He went to sit at his official desk and an animated discussion ensued. During the course of this he turned to me for my opinion but I had no idea of what they were talking in Arabic. My friends then explained that I was a foreigner. He expressed surprise and said I looked like a Yemeni but a long one, meaning that I was tall in comparison with the average Yemeni man. Since I was now confirmed as a foreigner, he needed to show hospitality. He rummaged in his drawer and found an apple which he vigorously cleaned on his shabby sarong and offered it to me. It was no time to refuse this man who now had us in his control. I ate the apple with seeming relish while tea was ordered for all of us. The discussion ended when the sum of money due to the police was agreed and money changed hands and the letter of authority signed and handed over. We were now all smiles and the atmosphere was very cordial.

We went back to the hospital, handed the woman over to the Chinese man, and started our journey back to the main road. We now had another noisy argument in hand, to agree on the sum our friends should pay the bandits with us. Once this was settled and money again changed hands, the discussion was very friendly. They may have been old friends recalling happy anecdotes from the past. Soon we were near the road and the bandits wanted to leave us. We all got down from the vehicle to exchange fond farewells. The bandits kissed all of us in turn and expressed sadness over the parting. We all appeared moved by having to leave these fellows who would have murdered us without compunction or held us for ransom if we did not have the money to satisfy them.

Leaving Yemen through Aden was also an adventure. On arrival in Aden I would be met by the senior partner, Yeslam Salim Maasher. But since the police suspected all and sundry who dealt with foreigners, he would not speak to me in the open area in the airport. He would be recognised as he was a short stout man in sarong and coat wearing a red fez cap. He would walk to his car and I would follow him and enter the car. We would then exchange cordial greetings and talk inside the car. Once at the hotel, he would leave and I would find that my room was booked and paid for in advance. On one occasion, Yeslam Salim Maasher took a bold step. He came to my hotel at night and invited me out for dinner. We went to an old hotel from British colonial times and entered its large dining hall. It had about 40 tables, all laid out for diners, and a dance floor. But there were only about half a dozen men at two tables. There was a large stage at one end where a three-piece band played slow dance music beside a grand piano. A dozen attractive young women dressed in long Western-style skirts stood behind the musicians looking at the audience. This was, after all, a socially liberated communist society, quite distinct from ultra-conservative North Yemen. Perhaps the many Russian technicians in the country visited these places. A notice board near the stage carried the warning in large letters: “Men are forbidden to dance with men”. Salim urged me meet to take one of the girls and dance but I declined. The whole atmosphere was discouraging. We had a good dinner and called it a day.

In 1979 I left the multinational corporation and joined another business. The exports to Yemen from the company ground to a halt after that. The Shammakh brothers still occasionally corresponded with me. But the story has a sad ending. The Maasher business wanted a certain product from Sri Lanka. I found an exporter of this product in Colombo, also a Muslim family, and recommended them. Several exports were made on the basis of payment by Letters of Credit. But the exporter declined to ship one consignment after receiving the Letter of Credit on the grounds that raw material costs had increased. The Shammakhs’ requested the shipment urgently, offering to cover the increased costs with the next order. But the local exporter did not understand the Arab’s code of honour and that his word is his guarantee. My intervention on behalf of Maasher proved fruitless. They steadfastly refused delivery, demanding an immediate change of the Letter of Credit. I noted that my Yemeni friends were hurt by this lack of trust and I lost their friendship on this issue and the exporter lost the business.

Kenneth Abeywickrama

15 October 2010-10-14

Note by author: I include this travelogue without apology because I believe the best way to understand a society is not merely by studying reports and country data but additionally by getting to know the people personally.

[1] Imams claim descent from the son-in-law of Prophet Mohamed and are Shiite religious leaders.

[2] Qat contains cathomine, a mild natural amphetamine. Its effects wear off after a few hours.

Pictures of Yemen in the seventies

All rights to copy reserved. Publication omly allowed with the permission of the author.

Kenneth Abeywickrama

15 October 2010

| M.A. Akbar makbar3660@msn.com 173.169.125.241 |

Dear Kenneth: |

Dear Kenneth,

It is a fascinating story that I came across by incident. My name is Mohammed Maasher. Yeslam Maasher is my uncle, he died four months ago. I currently live in Manchester.

I found Kenneth’s following comment to be very striking:

“Long before the American neo-conservatives, and before President Ronald Reagan discovered that “Government is not a solution to our problem, government is the problem”, the Yemenis had agreed that “Less government is good government”. Following this credo, even in Ottoman times, the Central government confined itself to the cities while the real management of the country was in the hands of powerful local warlord tribal leaders, some of whom claimed to be Imams”

I don’t believe that Reagan was, by any standard, an intellectual. He was merely repeating what a speech writer had put in his mouth when he made that “Government is not the solution ………..” comment – a comment parroted even today by some conservative politicians, in spite of the fact that the financial crisis that America faced two years ago and is still reeling from, is a result of the implementation of the “Less government” policy.

Just came across this while trying to find a way to get to Hodeidah from Jeddah. Great reading. Thank you Kenneth.